What is “Science”?

What is “science”? Ever since the COVID-19 outbreak, the term has been thrown around by almost everyone. It’s used as a way to make it seem like your opinion is validated or that the opinion of others is not legitimate. I started writing this a few weeks ago and it seems like there have been two or three more announcements or major news stories made that reference science since then.

The actual definition of science, per the Oxford Dictionary (remember those?), is

“the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against the evidence obtained.”

Even the definition of science is vague at first glance, but if look carefully at the last few words, it becomes clear that you must test your theory against evidence before coming to a conclusion.

How one might go about the testing portion of the study is the most critical part. Getting science wrong has very real consequences. From vaccines, to climate change, to causes of autism, to alternative medicine and GMOs, the “science” is what we all must lean on to determine the truth. And to make decisions on how to live and what’s best for those that we care about.

Before I dig into how the scientific method is used, it’s important to distinguish where information on a topic comes from. Journal articles, the primary way science is communicated in higher education, are a different format than online news articles, social media posts or blogs and require a level of skill and are put under much more scrutiny.

A journal article is written by experts and published in an academic journal to share new research, theories, or findings with other professionals in a specific field. These articles are often reviewed by other experts before publication (peer review) and are considered a high-quality source of information.

The danger is that now that the world has search engines and AI, it’s not that difficult find a ”study” that shows the results that you believe or want to be true. For most people, that one study is enough proof for them. What constitutes enough proof? Unfortunately, spending hours in the research is the only way to truly get enough information to determine if the study you are referencing is legitimate.

You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, boring writing style and the unfamiliar words and terms. I felt this way years ago when I started digging deep into studies on fitness, nutrition and training techniques. Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school – my wife is in the middle of her clinical psychology doctoral program and can attest to this as well. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice. Which most people are not willing to take on.

Reading a journal article or research paper is a completely different process than reading a summary on social media or in an article on a website from your trusted news source. It’s even different than reading a book. You will have to read the sections (Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion) of the research in a different order than listed. You will likely have to read portions of it multiple times and even take notes like you are back in school studying for mid-term. I often go down rabbit holes looking up other papers that are referenced for some of the details. Does this sound like fun yet?

If you are still interested in learning how I suggest going about this, here are some things to consider before you read a journal article or research study:

- Who are the authors and what are their institutional affiliations.

- Some institutions (most universities) are well-respected. Others (The Discovery Institute or Center for American Progress for example) may sound like legitimate research institutions, but are actually agenda or financially-driven.

- Take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be found in Pubmed or on clarivate.com

- Note the date when the study was done. Knowing when the research was published helps you have an understanding of whether these are the most recent findings and how likely it is that further studies have taken place since.

- Determine who funded the study. Check the acknowledgments section of the paper for a specific funding statement. You can also look for grant numbers and use databases like NIH RePORTER to search for the funding agency. The biggest example was when the sugar industry paid scientists in the 1960s to publish research that downplayed the link between sugar and heart disease, shifting the focus to saturated fat instead, a narrative that influenced dietary guidelines for decades. Tobacco companies also funded many studies concluding that second hand smoke was not harmful.

INTRODUCTION

Once you feel convinced that research is from a credible source, start by reading the Introduction. The abstract is listed first but won’t tell you the whole story and if you just read this, you could misinterpret what the actual findings were (I’ve been guilty of this). Abstracts are a summary and interpretation of the entire study. I’m not saying to ignore the abstract but read it after you have dug into the research.

The introduction will also describe what the purpose of the study was. Using the scientific method, this would be the exact question the researchers were trying to solve and should be very specific. Sometimes you will see a headline about “research finds…”, but if you read deeper, that might not be the answer to their question and should give you a pause.

METHODS

Next read the methods section. This will tell you exactly what the authors did as part of this experiment. An experiment is designed to test the hypothesis in a reproducible way, collecting relevant data and observations. The methods should be directly aligned with the question they set out to answer. If they or other researchers can’t reproduce the exact method that was used, the results should not be valid.

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is thought of as the “gold-standard” method of research. It is a scientific study where participants are randomly assigned to either an intervention group or a control group to test the effectiveness of an intervention. A RCT cannot always be used due to ethical concerns, logistical limitations, or when the intervention affects a whole population rather than individuals. Ethical issues arise when withholding an effective treatment from the control group is dangerous or when it's impossible to conduct a study without affecting the participants' lives. Logistical problems include situations where interventions target entire communities, and the control group can be contaminated by the intervention's effects.

Implementing and managing a full RCT can be very costly and time-consuming, especially for interventions that are intended to be implemented over a long period. They may not be feasible for all research projects.

RESULTS

Next is the most important part in my opinion. The Results.

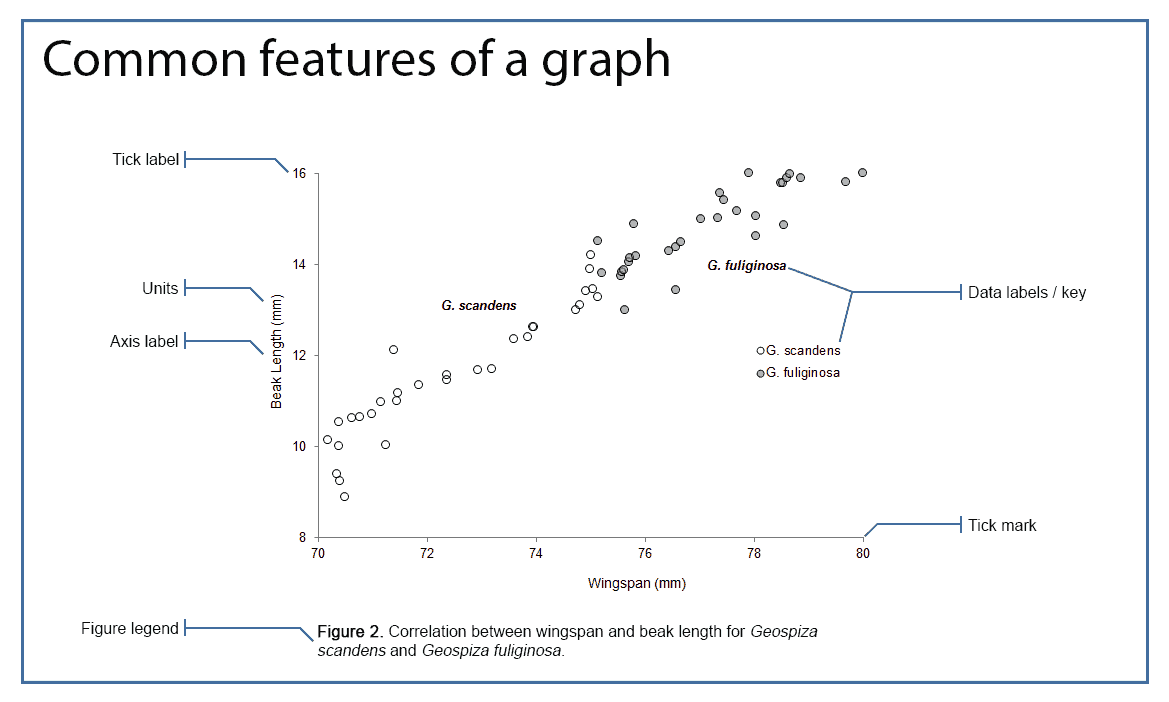

This is one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment. Usually, the results are summarized in the figures and tables (you know I love charts and graphs). Pay careful attention to these.

The results can be hard to read. Especially if statistics are involved. They are usually way more complicated than that high school Statistics class we took. Even for those of us that took higher-level Stats in college, that was likely a long time ago and interpreting statistical results can be confusing. Below are some things to pay attention to in the results section:

- Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings.

- A result is "statistically significant" when the observation is unlikely to have occurred by random chance, leading researchers to reject the null hypothesis (no relationship or effect) and accept the alternative hypothesis.

- A “non-significant” result does not mean there is no effect. It means the study failed to prove one with sufficient confidence. This could be due to a small sample size, for instance, which makes it difficult to detect a true effect.

- The sample size. Was the study conducted on 10, or 100,000 people? This is a big one for me. Depending on the subject of the study, a large sample size may be difficult, but if it’s something that is more common in society or has been around a while, I usually discredit small sample size studies.

- What do YOU think the results show? If you are still reading this post, you are likely a pretty smart person. Use your logical mind to interpret the results on your own. What conclusion do you think they show? Maybe once you read the researcher’s interpretation and conclusion, you will change your mind, but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those held by others – even the authors of the study.

CONCLUSION

Now read the Conclusion/Discussion/Interpretation section.

Do you agree with the conclusion the authors made? Do they call out any weaknesses in their own study? If not, that’s a red flag. You can always think of ways to do it better if you had the chance to start over. The researchers should tell you what they missed.

This is where it is important to remember the phrase “causation does not equal correlation”. Observing that two things change together (correlation) doesn't automatically mean one causes the other; a third, unobserved factor, random chance, or reverse causation could be responsible for the relationship. Mistaking correlation for causation can lead to incorrect conclusions and misguided decisions.

Some examples that help this make sense:

- Ice cream sales and drowning: Both increase in the summer, but a third factor (hot weather) causes people to buy more ice cream and go swimming more, leading to both increases.

- Firemen and damage: More firemen at a fire correlate with more damage, but the fire itself is the cause of both the damage and the larger number of firemen needed.

- Lighters and lung cancer: The number of people with lighters correlates with the number of people with lung cancer, but the real cause is smoking, which is correlated with both phenomena.

A research study could do everything correct, but draw a conclusion based incorrectly on ignoring or not exploring a possible third factor. Even top Scientists struggle with the difference between correlation and causation. And a few years back, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University collaborated with researchers in Sweden to study Autism. In the first part of a study, they compared children who had been exposed to Tylenol - which is a trade name for the drug acetaminophen - with children who had not been exposed while in the womb. And they did see a small statistical association linking Tylenol use to autism. But autism is a very hereditary condition, and association is not causation. So they tried to drill down on this question by comparing siblings. Specifically, they looked at cases where one child had been exposed to acetaminophen during pregnancy and the other had not.

When they did the sibling analysis, the association completely disappeared. In other words, the association was not a causal one, and it was most likely due to other factors like genetics, infections, fevers, or something else.

So yes, there is a connection between autism and Tylenol use by the mother, but it appears to be a correlation and not the cause. At least in this particular study. This is an example of how it is easy to prioritize studies showing a correlation while giving insufficient weight to the more scientifically robust sibling-controlled analysis that demonstrated no causation. If you go into the research with the expectation of a certain result, you can easily convince yourself that you see that result.

As mentioned previously, the gold standard for science is the randomized controlled trial, and you can't exactly do this with pregnant women due to ethical concerns around the health of the mother and fetus.

This is not meant to be a political post, but I wanted to use a relevant and timely example of causation does not equal correlation.

ABSTRACT

Finally, go read the Abstract. Does it read like you thought it would based on the Methods, Results, and Conclusions?

Another good practice is to type the exact title of the Journal Article or Research Study title into a search engine to see what comes up. Sometimes you will come across someone (an expert in the field) else’s interpretation of the results or something that was missed in the methods that you may not have realized but someone else did.

I also like to search for a systematic review or meta-analysis on the subject or specific question being researched.

A systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of all available studies on a specific research question, while a meta-analysis is the combination of results from multiple studies to produce a more precise, combined estimate of an effect.

All meta-analyses are part of a systematic review, but not all systematic reviews include a meta-analysis. If there is a conclusion reached through the meta-analysis, I have a lot more confidence in the results than if it’s just one or even two studies reaching that conclusion.

Reading and interpreting a journal article is challenging because these papers are written for experts in the field, not the general public. If you want to put in the time and energy to become an expert in any field of study, the rewards are endless. However, I know that most people do not have the time or energy to do this, so I recommend you find a subject matter expert you can trust.

Someone can become a subject matter expert (SME) through a combination of specialized knowledge, experience, formal education, and establishing themselves as the go-to authority in a specific field. They demonstrate expertise by having a deep understanding of complex topics, providing actionable insights, and possessing strong problem-solving skills within their niche. Usually it someone that is very passionate about a subject and you can see that they have devoted a good portion of their life to it.

No comments yet.